In “artificial intelligence”, there’s “art”: is its market ready to leverage it?

Imagine a world where an app on your phone predicts how much the painting you just bought will be worth in two years, where forgers trade paintbrushes for 3D printers, and where robots are the hippest artists in town. And it all started with a simple internet connection… (You can read the original French version of this article here)

Much has been written about the “digitalization” of the art market, from online auctions and the influence of social networks to the ubiquity of smartphones. These developments have one common consequence: an exponential rise in the volume of information produced.

Information is crucial for all markets, and the art market is no exception. Dealers and buyers need to collect data concerning collectors, artworks, past prices, exhibitions…For a market often presented as opaque (non-public prices outside the auction rooms, importance of relationships), analyzing and processing old and new information is crucial. And this is precisely one of the promises of artificial intelligence.

Artificial intelligence is often defined as the acquisition by computers of cognitive skills traditionally associated with humans, such as the ability to learn, autonomy in an environment, or even (one day?) consciousness.

Among the technologies falling under the artificial intelligence umbrella, machine learning is the process of extracting information from big data. It uses techniques to sort through large data sets and gives computers the ability to learn from them, ie — from a large amount of data, the system “learns” to recognize a cat’s image. For projects requiring a higher degree of complexity, such as beating a human champion at the game of Go, “deep learning”, which is based on interaction networks mimicking the neural functions of the brain, steps in.

Artificial intelligence is not limited to the (large) family of machine learning, but deterministic AI or decision support systems are not currently used by the art market. Our enquiry will therefore focus on two main applications of artificial intelligence for the art market: prediction and authentication.

AI, tomorrow’s fortune-teller?

The purchase of a work of art, while theoretically an expression of passion for the artifact, is also motivated by the price that can be expected from its resale. Will art advisors be replaced by algorithms that instantly draw from databases to aggregate the behavior of thousands of consumers? We are not there yet, but a first study to this effect was launched in 2014 by Ahmed Hosny, Jili Huang, and Yingyi Wang as part of a student project. Entitled The Green Canvas, their model aimed to predict the value of a painting, by comparing the prices of the Blouin Art Sales index and the elements of the work such as color, contrast, the presence of a face, etc. After running the model on 35,407 paintings valued at almost ten billion dollars, the conclusions are rather modest: saturated colors lead to lower prices, and auction records take place on the same dates as large-scale exhibitions. An analysis based specifically on Picasso results in a prediction of 0.58, measured as the correlation between the actual price and the predicted price. That is, the system is accurate just over every other time…

The 2018 Hiscox Digital Art Market Report estimates that “the consumer of the online art market will be increasingly demanding on price transparency — the rise of big data combined with artificial intelligence could offer more sophisticated techniques to understand and measure the value of an art object”. Visual recognition has indeed improved since 2014, and a refined model incorporating even more data would be possible. But this would have a cost, because the collection (scraping) and especially the formatting (cleaning) of the data to make them usable by the program cannot be done without significant human work. “The art market is ten or fifteen years behind the business or sports world in terms of technology adoption,” says Jason Bailey, founder of the Artnome blog and art database. “This is partly due to the lack of structured information about the works”, continues the man who defines himself as an “art nerd”. With the data he has been collecting and the increase in computing power, he hopes to develop a system that would identify undervalued works and ultimately lead to a more efficient market. “It worked for baseball, as proved by Moneyball [a book published in 2003 that documents the statistical analyses of a coach leading his team to stardom], why not in the art world?”

User behavior is the new gold

Earlier in 2018, Sotheby’s acquired the start-up Thread Genius, founded in 2015 by two former Spotify engineers. The company, initially active in the fashion industry, uses image recognition to understand consumers’ tastes and “push” similar visuals. This purchase comes two years after the acquisition of the Mei Moses Art Indices, a database of nearly 50,000 repeated auctions in 8 categories. A valuable dataset to be integrated into the Thread Genius system? Tim Schneider, who runs the columns the The Gray Market on Artnet, highlights the limits of a service like Thread Genius in a market where goods are not substitutable. Two visually similar sculptures by artists with different art-status would not get the same price. According to Schneider, this visually-powered feature is intended primarily for beginning, uninformed buyers. This does not mean that it is a bad purchase for Sotheby’s, which could use it to attract new customers.

The art market is not alone in being interest in the behavior of “visitors”. In 2017, the Data & Musée project was launched, aiming to “study online and in situ behavior, in order to make better use of data and promote exhibitions based on user profile, for example”, explains Philippe Rivière, head of digital and communication services at Paris Musées (the consortium of Museums funded by the City of Paris).

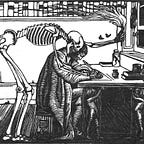

AI detective-scholars track down fakes

Artificial intelligence is well on its way to deciphering the behavior of market players, but it is also turning towards the very heart of the market: the artwork. Out go the trials where specialists argue about the authenticity of a De Vinci, in comes expert software?

In November 2017, Ahmed Elgammal of Rutgers University presented a tool that identifies fakes based on an reading of strokes that make up a drawing. A signature by touch theory that dates back to the 1950s… but the high number of lines to analyze made the task too difficult for humans. The rtificial intelligence he developped recognizes the artist 80% of the times, and is even able to detect fakes from a single brush stroke! As with The Green Canvas, the upcoming challenge is the change of scale. Researchers are now working on paintings (more complex than a line drawing!) and the issue of an artist’s style evolving during his or her career.

The Replica project, launched in 2015 by the Digital Humanities Laboratory of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, seeks to develop the first search engine specifically designed to explore art collections. Using artificial intelligence to extract more data from images, it connects thousands of works of art based on elements such as form or pattern, something traditional search engines are not able to do. If the project is primarily aimed at art historians and research, it could also be used for a stylistic analysis to demonstrate the authenticity of a work.

Roman Komarek, a Czech entrepreneur, intends to ensure that once the work has been authenticated, it does not undergo any alteration during its life cycle. His company Veracity Protocol is developing a decentralized IT infrastructure that combines the mathematical imprint of a photograph of the work (or any other object) with a “passport” that guarantees its origin.

Is artificial intelligence creative?

Collecting data and analyzing it is great, making art out of is… awesome? The Parisian collective Obvious uses an “artistic approach where the machine is in charge of the creative part,” according to Pierre Fautrel, one of the three team members, with Hugo Caselles-Dupré and Gauthier Vernier. Using Generative Antagonistic Networks (GAN for short), the collective creates portraits of a fake 18th century family. The technique consists of running two neural networks in parallel: one generates images and the other checks whether they are known or not. Both networks learn what a portrait looks like from a large database. Once the “creative” network succeeds in fooling the “control” network by presenting it with a portrait it created, the process is completed. The portrait is then ink-jet printed and framed. The result may have convinced the machine, but humans quickly spot a certain strangeness: “we make conceptual art, people are rarely subjugated by the result”, admits Pierre Fautrel. Another point of improvement, the database that feeds the generator network is composed mainly of Western works, and the collective wishes to incorporate visuals from Asia for other projects.

The portrait of the Earl of Belamy will be the first work generated by AI to be presented by an auction house at the Christie’s New York “Prints and Photography” sale in October 2018. However, this is not the first auction of its kind. In 2016, 29 paintings made by Google’s artificial intelligence went under the hammer for a charity sale in San Francisco, the most expensive painting going for $8,000 (the low estimate of Obvious’s portrait by Christie’s).

But the Christie’s sale should be a milestone, as it symbolizes access to the “established” art market [UPADTE: and because it reached the record price of $423, 000]. Art and technology networks have developed at a certain distance from the art market, burgeoning within universities ( the Art and Science Chair which brings together the Polytechnic School and the National Superior School of Decorative Arts in Paris) or dedicated festivals such as Ars Electronica in Austria.

Anne-Cécile Worms, co-founder (with Ada Fizir) and president of the ArtJaws marketplace, dedicated to new media artists, could only agree. “For the moment collectors are still buying works that hang on the wall, we are accompanying them in the discovery of techart and issues such as the maintenance of the work”, she explains. “Artificial intelligence is of course one of the technologies that interests us, and we will soon present a curated section dedicated to this theme on the platform.” This king of educational effort could be reversed if the digital art market was to focus on another target, thinks Jason Bailey. “You have a growing class of engineers who earn a good living and are interested in art, but they can be intimidated by the art world. Except that if they go to an exhibition or auction presenting algorithmic works they will be the smartest person in the room! There is a market here”, he concludes.

Dominique Moulon, art critic and independent curator, warns about the ambiguity of works that use these technologies. “The Next Rembrandt, a painting generated by a program “in the manner of” is typically a fake work… we are in a logic of forgery”, he bemoans. “The most interesting works are those that take technologies as a societal subject rather than those that use them.”

Beyond art?

So — surprise! — machines are not yet ready to replace humans. This is where all the ambiguity of artificial intelligence, which plays on the fantasy and threat of a new kind of intelligence that would surpass its creator, lies. The technical complexity involved can quickly transform a “simple” algorithm into a “promise of revolution”, and few are those who can — and want to — reveal the exaggerations.

Continuing to leapfrog over the notions of creativity, technology and borders, we land at virtual territories far from the archipelago of the art market. In October 2017, designer Frank Lantz launched a game that consists of producing paper clips by controlling a few increasingly complex variables. The game ends with the destruction of the world: the AI you trained followed its goal to the end. Inspired by the book Superintelligence by philosopher Nick Bostrom, which presents a similar example, the game was tested (and often finished) by 450,000 people in ten days. Not art, not science, not entertainment: welcome to the future.

This article was originally published in AMA’s Art and Finance Issue in October 2018.